AERATED

LAGOON TECHNOLOGY

by

Linvil G. Rich

Alumni Professor Emeritus

Department of Environmental

Engineering and Science

Clemson University -

Clemson, SC 29634-0919 USA

Email: lrich@clemson.edu;

Tel. (864) 656-5575; Fax (864) 656-0672

Technical Number 1

EFFLUENT BOD5

A MISLEADING PARAMETER FOR THE PERFORMANCE

OF AERATED LAGOONS TREATING MUNICIPAL WASTEWATERS

In

spite of the fact that effluent BOD5 is a key parameter in many discharge

permits for aerated lagoons, it is the most misleading. Most effluent

BOD5 data are flawed as the result of being inflated by nitrification

that occurs in the BOD5 test itself. It has been reported that as many as 60

percent of the BOD5 violations nationally may have been caused by nitrification

in the BOD5 test rather than by improper design or operation (Hall and Foxen

1983). Consequently, millions of dollars may have been spent needlessly on new

treatment facilities.

The total BOD of a wastewater is composed of two components – a

carbonaceous oxygen demand and a nitrogenous oxygen demand.

Traditionally, because of the slow growth rates of those organisms that exert

the nitrogenous demand, it has been assumed that no nitrogenous demand is

exerted during the 5-day BOD5 test. Although, such assumption is valid when the

test is performed on untreated municipal wastewaters, it is not valid when

performed on secondary effluents, especially those from aerated lagoons. The

BOD5 of effluents from the latter are almost always inflated by a nitrogenous

component. Moreover, unlike the carbonaceous demand which is proportional to the

concentration of the biodegradable carbon constituents in the effluent, the

nitrogenous demand exerted during the 5-day test is proportional to the number

of nitrifying organisms that happen to be caught in the sample being tested.

Thus the argument that the test provides insight on the impact that the effluent

will have on the receiving water can not be defended. Neither can the practice

of making waste-load allocations from models that contain both a BOD5 (assumed

to be a measure of the carbonaceous demand) and a nitrogenous demand.

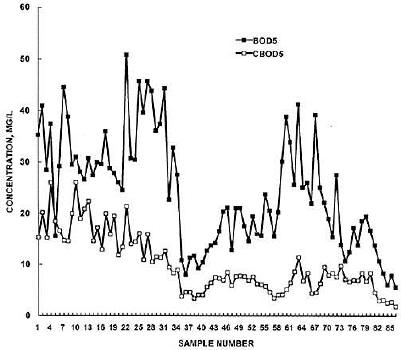

The

severity of the problem is illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2. Figure 1 compares the

effluent BOD5 with the CBOD5 (carbonaceous component of the BOD5). The CBOD5 is

determined by using a nitrification suppressant in the BOD5 test. Figure 2

compares the two parameters in filtered samples. Note should taken of the

magnitude of the nitrification factor in the 5-day test. Similar magnitudes are

observed in effluents from aerated lagoons in warmer climates.

Figure 1

click on graph to

enlarge

Figure 1 above illustrates Effluent BOD5 and CBOD5 data from an aerated lagoon

system in Maine that treats a domestic wastewater. (Courtesy of George Bloom,

Woodard and Curran, Engrs. Taken from Rich (1999))

Figure 2

click on graph to

enlarge

Nitrification in the BOD5 test has been thoroughly

researched and documented (Young 1973; Dague 1981; Barth 1981; Carter 1983;

Chapman et al. 1991). Such nitrification can be eliminated by the use of

commercially available nitrification inhibitors, a practice recommended by

Standard Methods (1995). Chapman et al. (1991) demonstrated that by cleaning the

sampler tubing weekly with chlorine bleach, nitrification in the BOD5 test can

be reduced. The U.S. EPA has given their approval to the use of a nitrification

inhibitor, provided that the effluent permit states the limit in terms of the

CBOD5 instead of the BOD5. Arguing that secondary BOD5 limits were initially

established on the basis of values flawed by nitrification, the EPA has

suggested that the CBOD5 limit for secondary treatment be 25 mg/L rather than

the 30 mg/L allowed when the limit is stated in terms of BOD5 (Hall and Foxen

1983). Considering the fact that the nitrification component of the BOD5 is

generally at least 5 mg/L and frequently as high as 50 mg/L, the 25 mg/L limit

appears to impose no handicap.

In summary, BOD5 is an ambiguous parameter when

applied to secondary effluents, especially those of aerated lagoons, and should

not be used. Instead, use should be made of the CBOD5 test which specifically

measures the concentration of the biodegradable carbonaceous materials.

REFERENCES

Barth,

E. F. (1981). “To inhibit or not to inhibit: that is the question.” J. Wat.

Pollut. Control Fed., 53(11), 1651-1652.

Carter,

K. B. (1984). “30/30 hindsight.” J. Wat. Pollut. Control Fed., 56(4), 301-305.

Chapman

et al. (1991). “Minimizing the impact of nitrification in nitrifying

wastewaters.” Operations Forum, WPCF, Sept. 14-16.

Dague,

R. E. (1981). “Inhibition of nitrogenous BOD and treatment plant performance

evaluation.” J. Wat. Pollut. Control Fed., 53(12), 1738-1741.

Hall, J.

C. and Foxen, R. J. (1983). “Nitrification in the BOD test increases POTW

noncompliance.” J. Wat. Pollut. Control Fed., 55(12), 1461-1469.

Rich, L.

G. (1999). High Performance Aerated Lagoon Systems. American Academy of

Environmental Engineers.

Young,

J. C. (1973). “Chemical methods for nitrification control.” J. Wat. Pollut.

Control Fed., 45(4), 637-646.

|